Originally featured on Univision.com

According to a new study, 75% of American women between the ages of 18 and 30 don’t know any older women who have recovered fully from eating disorders and remained in recovery, which is discouraging them about their own prospects for a full life that is free from food and weight obsessions.

According to a new study, 75% of American women between the ages of 18 and 30 don’t know any older women who have recovered fully from eating disorders and remained in recovery, which is discouraging them about their own prospects for a full life that is free from food and weight obsessions.

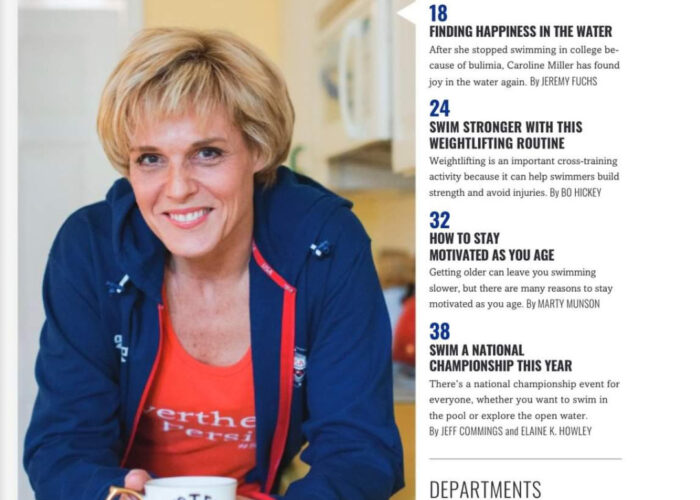

As a result of these findings, perhaps the image of the girl-woman who stops eating because she wants to look like a Barbie should be replaced when representing victims of anorexia and bulimia, according to Caroline Adams Miller, MAPP, an expert who has written several best-selling books about her own recovery from bulimia.

A few days before the onset of “National Eating Disorders Awareness Week” (February 23 to March 1), a new SurveyMonkey poll commissioned by Miller reveals that despite decades of research, help and awareness about genetic and environmental triggers for eating disorders, as well as ways to treat them, there aren’t as many positive outcomes as some may have hoped that could light the way for the next generation. In fact, other well-known research has found 43% more middle-aged women are seeking help now for eating disorders because they have either never gotten better, or they have developed eating disorders at midlife.

The survey, conducted on U.S. women between 18 and 30 years, found that 75% do not know a woman who has managed to overcome an eating disorder and remain in recovery, 60% of them believe their mothers are unhappy with their bodies, and that too few of those mothers and female role models have passed along positive behaviors around food and weight.

In addition, 55% of young women surveyed admitted that they do not believe they can live a life “free” of weight issues.

According to Caroline Adams Miller, MAPP, a pioneer in the eating disorder field and author of “My Name is Caroline” (Doubleday, 1988), the first major autobiography of a bulimia survivor, as well as its new sequel, “Positively Caroline” (Cogent 2013), which is the first autobiography by someone who has been in unbroken recovery for 30 years, these findings should remind eating disorder advocates of the importance of helping older women get and stay in recovery. She believes this would help young women have more hope that their early efforts to get well would be successful throughout many of the hardest years of an adult women’s life, which often include pregnancy, childrearing, professional challenges and hormonal/life shifts.

She adds, “If there aren’t enough people who have recovered for several decades, how will the next generation have any hope that their lives can and will improve in the areas of body weight and food obsession if they put in the work to get better now?”