September 29, 2012

Last week I had the privilege of going back to Harvard University to spend three packed days with Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey, who have spent decades developing and refining their own unique approach to personal transformation. Called “Immunity to Change” (ITC), they specialize in going deeper than many other modalities to discover what “hidden commitments” exist to prevent someone from making headway on important goals.

Their work has been featured in many prominent places, ranging from the annual Harvard Coaching Conference, where I first experienced Kegan in a fascinating afternoon workshop last year, to the New York Times business section, which enthusiastically profiled their work in several corporations earlier this year.

As someone who specializes in goal-setting and change, including using Positive Psychology research, this training added a new level of knowledge to my tool kit and I’m looking forward to using it in specific ways in targeted situations with clients, students and groups. It’s intriguing where the ITC breaks away from what many of us have been taught, and it’s worth getting a taste of it because it’s so different. Here’s an example of how it works:

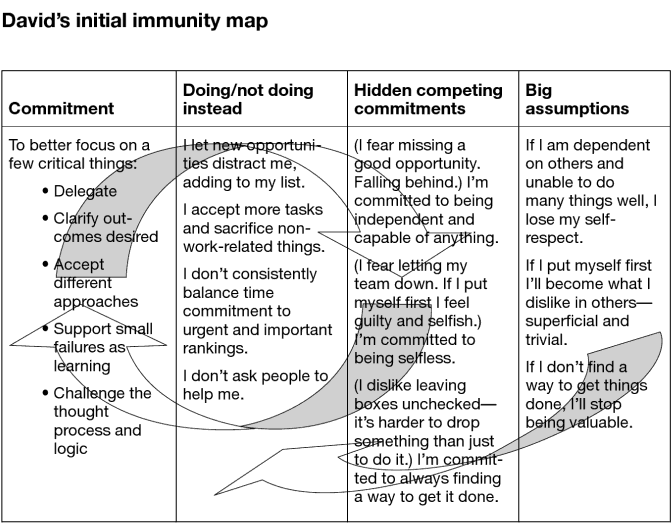

First, you identify an improvement goal. It could be becoming a better communicator at work, being less critical of family members, or even losing weight. The only criteria are that it’s about you and no one else (it positively “implicates” you), it is important to you (at least a 4 or 5 on a scale of 1 to 5), and there is room for improvement. Okay, that’s standard enough.

Next, another standard approach to change: list all of the things you are doing or not doing that make change hard, if not impossible. The list has to include things you are actually doing or not doing, and not things you are thinking. If it’s losing weight you could list statements like “I eat second helpings even when I’m not hungry.” If it’s about becoming a better communicator, you could write, “I don’t take the time to answer questions if I don’t think they are important.”

In the third column of the ITC method, things get interesting. The first thing you do is put statements in a “Worry Box” that bring to mind the dreaded image if you do the opposite of the column two behaviors. This could include “I’m worried that if I don’t eat two helpings, I will offend the cook and they won’t like me.” For the person who wants to communicate better, it could be “I’m worried that if I entertain questions, I won’t be seen as authoritative.”

Directly under the worry box, you convert the worries into “hidden commitments” that make your column two behaviors utterly sensible. For example, “I’m committed to always eating more than I want because I’m afraid I won’t be liked if I stop with one helping.” Kegan and Lahey call the awarenesses that result from realizing your “hidden commitments” the commitments that “have us” and essentially create an elegant “immune system” that completely protects us from opening ourselves up to getting hurt.

Directly under the worry box, you convert the worries into “hidden commitments” that make your column two behaviors utterly sensible. For example, “I’m committed to always eating more than I want because I’m afraid I won’t be liked if I stop with one helping.” Kegan and Lahey call the awarenesses that result from realizing your “hidden commitments” the commitments that “have us” and essentially create an elegant “immune system” that completely protects us from opening ourselves up to getting hurt.

The fourth column goes a bit further in defining what is going on with your immune system. What assumptions do you have about the world that will lead to a “big time bad” outcome for you if you actually do the behaviors that will make your self-improvement goal come true? Your assumption about the world goes something like this: “I assume that if I don’t eat second helpings, I won’t be liked.” Or “I assume that not being seen as authoritative could lead me to lose the respect of my colleagues, and I might become powerless.”

The last step is to create and carry out modest and safe experiments that challenge your assumptions. These experiments are the equivalent of “dipping your toe” into the waters of change, and not necessarily freaking yourself out by overturning your entire life. The idea is to gather data that will allow you to successfully challenge your assumptions, little by little, thus shifting your immune system from one that protects you from making changes to one that permits and protects the changes you want. A sample experiment based on the examples above would be eating just one helping, and noticing if anyone gets mad at you. Or if you stop and listen to others with curiosity, will you really lose respect and power?

I found my three days at the ITC training to be more unique than much of the training I’ve done in recent years. I saw adult men and women, who had traveled from as far as Australia, burst into tears as they painstakingly worked through their columns and had insights that were new and powerful. One woman explained her torrent of tears at lunch: “I suddenly realized that I don’t clean my closets because I’ve cleaned out the closets of many people who have died in my life, and my assumption is that no clutter equals death.” She looked stunned as she related her story to me. Her job was to go home and tackle the clutter, little by little, particularly in her closets, to consciously shift her emotions by seeing that she remained alive and healthy through the process.

While this knowledge is new to me, and clearly takes time to absorb and teach, I’m excited that I’ve been able to add something so different and healing to my work with people who are looking for results in their lives. If you have been stymied for years in making some changes in your life that you know would make you more effective, I strongly suggest that you explore this work yourself or with someone who has been trained in this method. It could be the missing piece.

Great summary! Thank you for the write-up!

Thanks for the great sharing Caroline 🙂 While I was going through, I had that somewhat ominous feeling that it could totally strip me ‘naked’ and threaten my deepest core. I feel ITC is a structured approach to dive in oneself with radical honesty. Tackling the immunity bit by bit also speaks of managing challenges, building self control, self-esteem and self-confidence. Good model. One thing though is we need to be able to see through our blind spots and develop perspective. Exploring with another person in this case would help 🙂

I couldn’t agree more about the radical honesty comment, Chin. To really get value from this exercise, you need to go to places that are very uncomfortable, and that I’ve never experienced with another technique. It’s very powerful.