“A client of mine says she is mad about the coronavirus restrictions,” a therapist noted during a webinar I recently hosted. “How can grit help her in this situation?”

The therapist’s question touched on something that I’ve been pondering for weeks. Although “grit” is the word we often see being used to describe the heroism of frontline responders, I believe that there is a different type of grit that might be even more important right now for us to pay attention to because of its capacity to change lives, and even our culture, in momentous and overdue ways: “compassionate grit.”

As I see it, virtually everyone in the world is being called upon to develop this character strength, which I define as “the selfless pursuit of hard, meaningful goals – that you didn’t choose for yourself – but that make other people’s lives better,” whether they want to or not. Instead of the passion that is baked into the accomplishment of one’s own gritty goals, we’re being tasked to embody compassion so that we will take on daily hardships of all types for people we will never know, and to do it for a long period of time.

Some people are handling this well – like designer Christian Siriano – who can’t make ordinary women’s apparel but who is suddenly sewing masks for hospitals. Likewise, restaurant owner John Foster Gunter, closed his Word of Mouth cafe in Louisiana, but decided to hand out free meals to the elderly every day. On the other hand, some have violated social distancing guidelines and community safety requests to protest stay-at-home orders, regardless of the death rates in their states or what harm might befall others, because they want their “freedom.”

In our highly-individualistic society that was founded on principles of independence, the clash between those who value personal liberty more than protecting the welfare of others was inevitable. Nothing in our lifetimes has prepared us for this difficult period. The novel coronavirus stands in stark contrast to every other global catastrophe of the last 100 years, including the polio virus, in terms of reach and deadly potential. It has infected every home in every country of the world with anxiety, loss, fear or death.

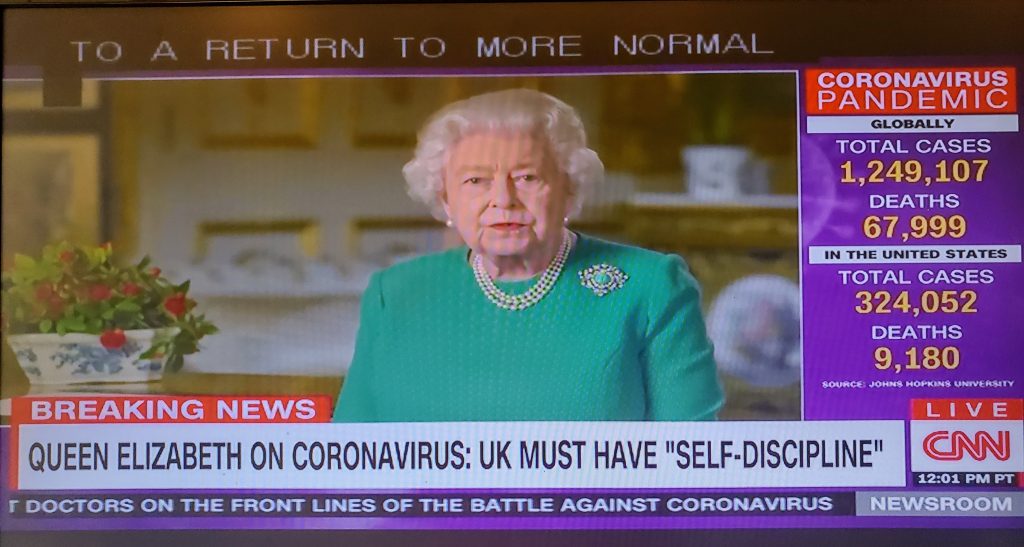

Since no one is immune from its impact, the reality that we are all in this battle together, and that we need each other’s love and cooperation, is requiring a societal shift that is only seen during the rare historical periods when accepting long-term personal hardship for community good occurs. One such example were the blackout restrictions placed on British citizens for six years during World War II, which Queen Elizabeth II referenced in her recent national address. She reminded the country to “self-discipline” so that future generations could look back with the same type of national pride that they have for the men and women of the 1940’s who labored by day in enclosed fluorescent-lit factories without windows, and who navigated roads and sidewalks without any light at night.

The only period of my life that is remotely reminiscent of what I feel now are the three weeks in October 2002 when two snipers terrorized the Maryland/DC/Virginia region with random attacks that included assassinating a man riding on a lawn mower and killing a Home Depot shopper in a parking lot. No one was safe and everyone was a potential victim, so we were united in changing how we pumped gas, avoided windows and canceled unnecessary public gatherings, including pumpkin-picking.

Similar to today’s wall-to-wall coverage, every television channel carried hours of breaking news and dire warnings; as much as we wanted to tune it all out, we had to remain glued to the news so that we had the latest information that could help us stay safe. To this day, I still scan the treetops for danger when I pump gas in the suburbs.

The uniqueness of this current coronavirus situation and how people are responding to it is what precipitated my need to identify a type of grit that never occurred to me while researching and writing Getting Grit (SoundsTrue 2017). “Good grit” is the passionate pursuit of hard, individually-selected goals that require years of resilience, patience and humility. When people knowingly enter a profession whose purpose is to serve others, they call upon this authentic grit to do whatever it takes to show up for work, dig deeper than they thought possible, and cross unimaginable emotional finish lines that would fell most others. Because these are personal quests invigorated by intrinsic motivation, staying the course is easier than if someone had just ordered them to do these jobs or pursue these goals.

But what about the rest of us – the men and women who didn’t sign up for selfless professional occupations? What if the grit we are being asked to exhibit, day in and day out, for an indeterminate period of time, is for other people’s hard goals and not our own? What if this type of sacrifice, which may or may not help us in the long run, is something that we’ve never been asked to cultivate?

What if the unfamiliar combination of feelings of frustration, anger, exasperation, loneliness, sadness, bitterness, confusion and anxiety are not just because we’re overwhelmed by the enormity and scariness of the disease sweeping the world, but also because a new character muscle has to be developed to survive the pandemic with kindness, resilience, self-regulation and pride?

In my field, Positive Psychology, it’s often said that happiness can be summarized with the phrase, “other people matter.” The time to really live up to this catchy slogan is upon us. Can we give up our own short-term gains for the long-term well-being of others? Is it possible to transition from a “Me Me Me” culture to a “We We We” outlook? Can we put aside our knee-jerk opinions and instead rely upon sober data to inform our actions? Can we do what the Dalai Lama once noted: “Our prime purpose in life is to help others. And if you can’t help them, at least don’t hurt them”?

Not only do I believe that we can do it, I think we already are the process of becoming better, more compassionate, people as the death toll continues to climb all over the world and hopes of a vaccine remain distant. All around me I see signs of contagiously positive behavior that is awing and inspiring others to dig deeper into their own emotional reserves and override personal disappointments with the joy of making a difference for others. For example, my Sunday morning Masters swim coach, Ryan Jolley, a senior at American University in Washington, D.C., started a line of handmade “RyDye Covid-19” masks instead of grousing about not having a carefree senior spring in college. Within weeks, she had raised $2000 for Project C.U.R.E., a non-profit organization that provides masks, gloves and other protective gear for hospital workers.

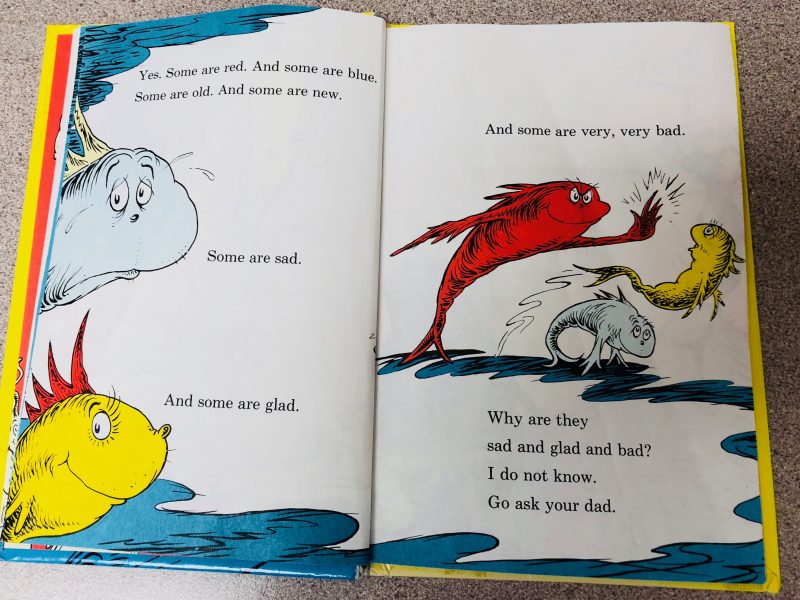

If you are feeling “mad sad bad” about what you are going without right now, here are some ways you can develop compassionate grit, which will make it easier for you to withstand the weeks and months – and possibly years – of hardship that lie ahead for all of us, and that may never resemble the “normal” we once knew. (An added bonus of becoming more of a “giver” was recently detailed by Adam Grant in the New York Times, who assembled the studies that showed that being altruistic is associated with higher intelligence!)

- Try “lovingkindness” meditation, which revolves around sending love and good wishes to yourself and others, including people who are difficult to love. Many apps and websites offer free guided meditations to get you started. The Insight Meditation Society has many resources to draw upon, for example.

- Read or watch any of the personal accounts of what it’s like to be infected with, or care for a patient with, the coronavirus to better understand the heartbreak many are experiencing right now. One nurse detailed the pain of holding up a cellphone so that a woman could say her final goodbyes to her mother over Facetime. These stories change the pandemic from a chart of statistics to an emotional story that might shift your focus in a different way.

- Act “as if” you are compassionate and want to put the health and well-being of others ahead of your own grievances. This pretend technique is more powerful than many realize, and can even work when you are trying to persuade someone else to behave in a different way. Altercasting – asking someone if they are “willing” to play a role in which they do something they don’t want to do – has been found to be inordinately successful in getting someone to change.

Two years ago, I attended the World Government Summit in Dubai where I heard three astronauts discuss what it’s like to blast into space and live for many days without the traditional safety and support of their normal lives. I’ll never forget the wise words of one of these women, who said, “The further you are away from the Earth, the more comfortable you need to be in your own skin, because you’ll be relying on your inner resources to survive and thrive.”

In this brave, new world defined by the novel coronavirus, I think we are all astronauts, flying outside of our old lives. If we want to survive this scary orbit, we will have to develop the strength of compassionate grit tempered with the wisdom that other people matter. The defining moment of our lifetimes has arrived, and the way we meet it will mark us forever. Let’s make it count.