January 30, 2016

During a recent blizzard, and inspired by the snowfall, I hunkered down to watch “Everest,” a 2015 movie that documents one of the deadliest days in the history of Mount Everest mountaineering – May 11, 1996.

On that fateful day, which dawned with brilliant clarity – presaging what should have been a perfect opportunity to summit the world’s tallest mountain – eight people died, many needlessly. One of the people to perish was Yasuko Namba, a 47-year-old Japanese climber who became the oldest woman to summit the tallest peak on each continent, but who descended so late in the afternoon that she was blinded by a whiteout and couldn’t make her way back to camp. Namba’s obsessive passion for Everest led her to lose her life alone in an icy, unforgiving place fittingly called “the death zone.”

As tragic as this was, I watched with even more horror as the story of Doug Hansen, a climber who had missed reaching the summit in a previous year, unfolded. A postman in his forties from the state of Washington, Hansen struggled up the mountain in what he insisted was going to be his final attempt to get there because of the time and cost involved. Discouraged and barely able to walk as he got closer to the prize, he became doggedly obstinate when some members of his party, including Namba, crossed paths with him as they made their way back down the mountain after achieving their own summit goals.

Although urged to turn around by everyone because of the changing weather conditions and lateness of the day, Hansen begged his guide – Rob Hall – to let him make the attempt, anyway. Against his better judgment, and concerned about his climber going alone, Hall reluctantly agreed to turn around and help him get to the top, a move that ultimately cost both of them their lives. Although Hansen got what he wanted, lack of visibility, oxygen and other resources got the better of them in their unsuccessful attempt to descend to safety. In all, eleven people died in one of the deadliest days on the mountain.

Hansen is a classic case of “summit fever” – a condition mountaineers describe as the inability to make good decisions when the summit is in sight, but the conditions have changed so much that turning around is the better choice. A better term for this type of decision might be “stupid grit.”

In the research for my upcoming book, “Authentic Grit,” I encountered many stories like Hansen’s of “passion and persistence in pursuit of long-term goals,” Angela Duckworth’s definition of grit, that gave me pause. It’s not that there aren’t positive aspects to their stories that might induce people to attempt something hard: it’s that their stories offer more cautionary tales than inspiration, in my opinion.

As a result, I came up with a new definition for grit that I call “authentic grit,” which I call “passionate pursuit of hard goals that causes one to emotionally flourish, take positive risks, live without regret, and awe and inspire others.”

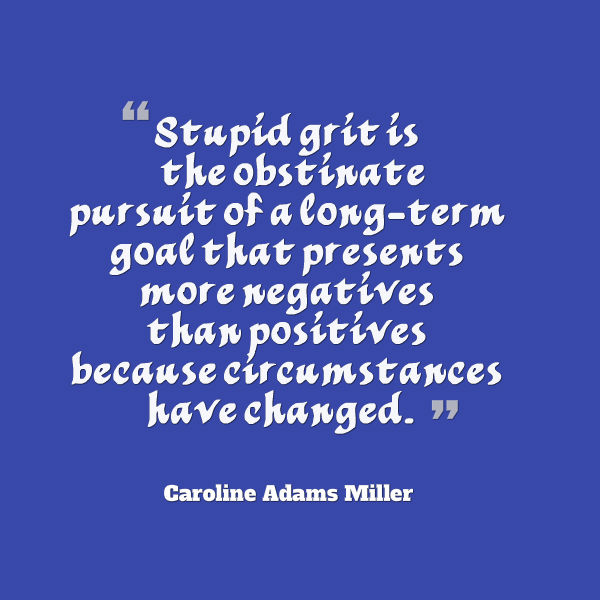

There is “stupid grit” everywhere, which I define “the obstinate pursuit of a long-term goal that presents more negatives than positives because circumstances have changed.” If we’re not careful, we will hear someone described as “gritty” and automatically assume that it is a compliment. There are situations, however, that we need to identify and study for the lessons we can learn, and in coming months I will share more stories – positive and negative – about various flavors of grit that I’ve discovered, including “faux grit,” “selfie grit,” “Mt. Rushmore grit,” and “Mt. Olympus grit.”

Do you have any examples to share of “stupid grit” that we can all learn from?

***

[…] When you drive forward to the detriment of yourself and others, I call that stupid grit,” explains best-selling author and positive psychology coach Caroline Adams Miller. […]

[…] When you drive forward to the detriment of yourself and others, I call that stupid grit ,” explains best-selling author and positive psychology coach Caroline Adams Miller. […]

As an avid outdoorswoman who loves to paddle and hike in the backcountry, I strongly agree with your analysis of the deaths you describe as examples of “stupid grit.” I’ve learned through experience that, when conditions become unexpectedly dangerous, it can take a lot more courage and strength of character to turn back than it takes to continue doggedly, but foolishly, onward. I’m really looking forward to reading your book!